- Music Theory Lesson 1; Middle C

- Music Theory Lesson 2:

reposted with kind permission

from Garbo’s blog

Push Start Music

It is not necessary to read music to play well. Many musical greats did not and do not. But if the magical system which is music is to be understandable, we have to have a “You Are Here” point on the location map.

Each day, we’ll build on where the notes on sheet music are and where they are on your instruments and where they are in our brains.

For me personally, it really helps me to retain information when there’s a hook or a grabbing point. So here’s one for the note we call Middle C.

In Western music, here is the list of playable musical notes: A, B-flat, B, C, C-sharp, D, E-flat, E, F, F-sharp and G. In a piece of music, there could be all of those notes, though probably not. Usually, some of these don’t show up. But the place they WOULD be is always the same whether the note is played or not. So we can count on it. It doesn’t move around. Everybody agrees where they would look for it.

Theoretically there are an infinite number of C notes, though of course only a few are within the range of human hearing. Have you ever heard the old song “Ain’t Got No Home?” The recording artist, Clarence “Frogman” Henry, sings “I can sing like a frog” and “I can sing like a girl.” So he sings the same tune exactly the same way, except up high like a woman with a soprano voice, down deep like a croaking frog, and sometimes in a medium way, in his natural singing range.

Each verse has the same notes, but some are low, some are in-between, and some are high. This could get really confusing if we didn’t all agree whether we are talking about a low note, a medium note, or a high note.

That’s where Middle C comes in. For our purposes here, what we want is to identify it and to be able to find it. I’ll say more about that tomorrow. But in the meantime, here’s how it BECAME Middle C:

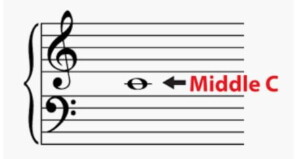

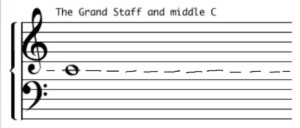

If you look at written music, especially for piano music, you’ll see two sets of five lines, separated with white space between them. This space is where Middle C lives. That circle is a whole note and the reason it has a line through the middle cutting it in half like a hamburger bun getting split to separate the lid from the bottom is to show you where the old line was erased.

The first people to use written-down music in Western music were monks who sang hymns. In the early part of the medieval era, there was no white space between the upper and lower lines. There was a solid line where I have drawn the dotted line in the illustration.

The singers kept losing their place. People were looking at a scrap of parchment with blurry blobs on ink put on with a quill, and then on top of that, they had to mentally count down –“Is that the ninth line or the eighth?” while they sang.

So by the 1200s, people were beginning to separate the high notes in the treble clef (“I can sing like a girl”) from the low notes in the bass clef (“I can sing like a frog”). They could have arranged things any way they wanted, but what they came up with was five lines over five lines with an imaginary line in the middle.

All the notes we consider bass notes are lower than Middle C and the notes we consider treble notes are higher than Middle C. Here’s what middle C sounds like on a piano:

NEXT LESSON>>> Why we even care where Middle C is if we want to play the euphonium or the banjo ukulele or whatever.